The answer to that probably depends on where you live, where you’re from and what you do for a living.

For those of us following developments in emerging technologies closely, it might seem like the past year has been the year in which news, discussion and debate about artificial intelligence (AI) has come to the fore. Deepfakes, AI surveillance, facial recognition, smart robotics, chatbots and social media bots have all been in the news, with some associated with some highly controversial issues. There’s also been plenty of debate about the impact of AI on political campaigning, data privacy, human rights, jobs, skills and, needless to say, the steady flow of industry messages about business efficiency.

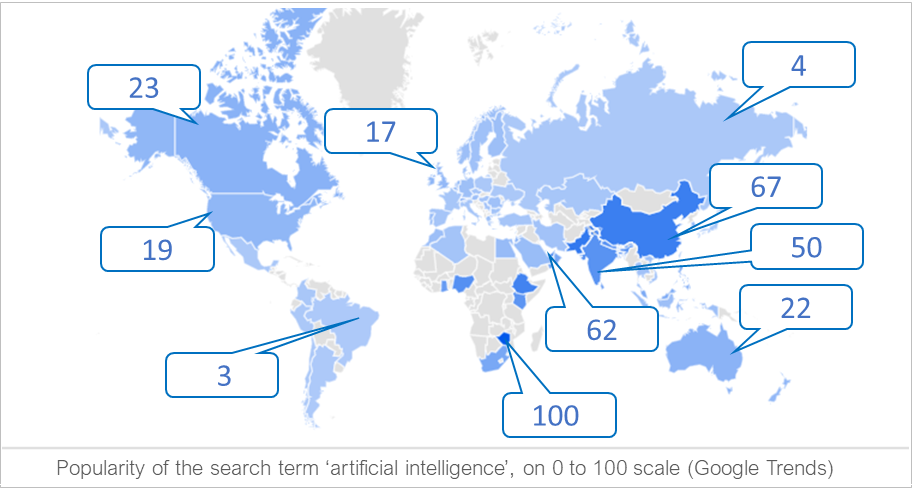

However, the truth is that the amount of attention that AI has received depends very much on which part of the world you live in and what you do for a living. One of the most interesting takeaways from looking at AI-related searches on Google over the past year is that many global search volumes for terms related to artificial intelligence haven’t changed that much, but the differences in interest shown from country-to-country is striking.

No prizes for guessing that China is among the countries that shows the most interest in artificial intelligence. Google Trends awards a score of 62 out of 100 for its search volume, despite the fact that Google’s services remain blocked for most Internet users in the country.

India (45), Pakistan (65) and the UAE’s (53) volumes of Google searches for artificial intelligence all compare favourably with China’s high level of interest. Although, for some reason Google Trends credits Zimbabwe (100) with being the country most interested in AI.

In Europe, the United Kingdom (15) and Ireland (17) are among the countries most interested in artificial intelligence, roughly on a par with the Netherlands (18), Switzerland (15), US (17), Australia (19) and New Zealand (15), while behind Canada (20) and South Africa (27).

Meanwhile, much of the world seems to be focused on other things. For those populations on the other side of the great digital divide, that’s perfectly understandable. Most of South America, Africa and a significant area of Asia appears to remain a backwater in terms of interest in AI. However, quite a number of European countries appear below 10 on Google Trend’s 0 to 100 scale, including France, Italy, Spain, Poland and others.

So, as we eagerly consume news and comment about how AI is going to change our world and herald sweeping changes that affect every aspect of our lives, it’s perhaps as well to remember that these changes won’t be uniform across the globe and, for many, artificial intelligence is going to seem largely irrelevant for a long time to come.

Note; figures from Google Trends 0 to 100 scale for search volume seem to change frequently, but the ranking of high to low volumes remain largely the same.

This story first appeared on Linkedin