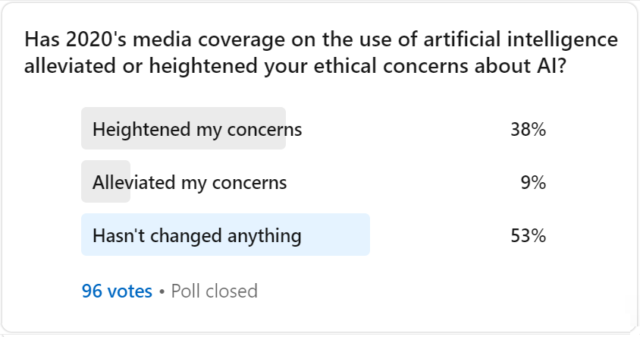

My New Year’s Linkedin poll about changes in how people feel about their ethical concerns regarding AI doesn’t prove much, but it does show that 2020 did little to ease those concerns.

Opinions and our level of understanding about artificial intelligence can vary a great deal from person to person. For example, I consider myself a bit of a technophile and an advocate of many technologies including AI, with a higher than average level of understanding. However, I harbour many concerns about the ethical application, usage and the lack of governance for some AI technologies. My knowledge doesn’t stop me having serious concerns, nor do those concerns stop me from seeing the benefits of technology applied well. I also expect my views on the solutions to ethical issues to differ from others. AI ethics is a complex subject.

So, my intention in running this limited Linkedin poll over the past week (96 people responded) was not to analyse the level of concern that people feel about AI, nor the reasons behind it, but simply whether the widepread media coverage about AI during the pandemic had either heightened or alleviated people’s concerns.

The results of the poll show that few people (9%) felt that their ethical concerns about AI were alleviated during 2020. Meanwhile, a significant proportion (38%) felt that 2020’s media coverage had actually heightened their ethical concerns about AI. We can’t guess the level of concern among the third and largest group – the 53% that voted 2020 ‘hasn’t changed anything’ – however, it’s clear that 2020 media coverage about AI brought no news to alleviate any concerns they might have either.

Media stories about the role of AI technologies in responding to the coronavirus pandemic began to appear early on in 2020, with governments, corporations and NGOs providing examples of where AI was being put to work and how it was benefiting citizens, customers, businesses, health systems, public services and society in general. Surely, this presented a golden opportunity for proponents of AI to build trust in its applications and technologies?

Automation and AI chat bots allowed private and public sector services, including healthcare systems, to handle customer needs as live person-to-person communications became more difficult to ensure. Meanwhile, credit was given to AI for helping to speed up data analysis, research and development to find new solutions, treatments and vaccines to protect society against the onslaught of Covid-19. Then there was the wave of digital adoption by retail companies (AI powered or not) in an effort to provide digital, contactless access to their services, boosting consumer confidence in services and increasing usage of online ordering and contactless payments.

On the whole, trust in the technology industry remains relatively high compared to other industries, but, nevertheless, trust is being eroded and it’s not a surprise that new, less understood and less regulated technologies such as AI are fueling concerns. Fear of AI-driven job losses is a popular concern, but so are privacy, security and data issues. However, many people around the world are broadly positive about AI, in particular those in Asia. According to Pew Research Center, two thirds or more of people surveyed in India, Japan, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan say that AI has been a good thing for society.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, AI’s public image has had wins and losses. For example, research from Amedeus found that 56% of Indians believe new technologies will boost their confidence in travel. Meanwhile, a study of National Health Service (NHS) workers in London found that although 70% believed that AI could be useful, 80% of participants believed that there could be serious privacy issues associated with its use. However, despite a relatively high level of trust in the US for government usage of facial recognition, the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 highlighted deep concerns, prompting Amazon, IBM and Microsoft to halt the sale of facial recognition to police forces.

Overall, I don’t think that AI has been seen as the widespread buffer to the spread of Covid-19 as it, perhaps, could have turned out to be. Renowned global AI expert Kai-Fu Lee commented in a webinar last month that AI wasn’t really prepared to make the decisive difference in combating the spread of the new coronavirus. With no grand victory over Covid-19 to attribute to AI, its role over the past year it’s understandable that there was no grand victory for AI’s public image either. Meanwhile, all the inconvenient questions about AI’s future and the overall lack of clear policies that fuel concerns about AI remain, some even attracting greater attention during the pandemic.

This article was first posted on Linkedin.